Here is the full transcript of the conversation between Fund/Build/Scale podcast host Walter Thompson and Rodrigo Liang, co-founder and CEO of SambaNova Systems:

Welcome to Fund/Build/Scale, a podcast that explores the tactics and strategies founders and investors are using to build early-stage startups. I’m your host, Walter Thompson.

Today, I’m talking to Rodrigo Liang, co-founder and CEO of SambaNova Systems.

Launched in 2017, SambaNova has raised more than a billion dollars to create a full-stack LLM platform.

Our conversation covered a lot of ground, including his thoughts on digging a competitive moat, product-led growth strategy for AI startups, and the importance of aligning the needs of customers with the technology you’re developing.

Before we wrapped up, I asked him to share some advice for founders who are fundraising in 2024 — and for anyone who’s thinking about joining an AI startup. More after this.

Fund/Build/Scale is sponsored by Mayfield, the early-stage venture capital firm that takes a people-first approach to helping founders build iconic companies.

The podcast is also sponsored by Securiti, pioneer of the Data Command Center, a centralized platform that enables the safe use of data and GenAI.

Walter Thompson

Thanks very much for joining me today. I appreciate it. Just a general question, what does SambaNova Systems do, and how did you initially get involved with the company? How did you initially connect with your co-founders?

Rodrigo Liang

So SambaNova, we’re an enterprise AI platform company, we’re focusing on helping companies train and deploy large AI, generative AI models, in a secure and private environment. And so when we started the company, there are two, three of us — two Stanford professors and myself — and we, we’ve known each other for years.

And so a lot of the common history, common threads really pulled us together, as we started thinking about this next wave of technology transitions that the world was starting to experience, which is artificial intelligence, machine learning. And now Gen AI.

Walter Thompson

How long did you know them before you decided to join up and become a founding team?

Rodrigo Liang

The three of us — Kunle Olukotun is a professor at Stanford, he’s been there for 35 years, I want to say thirty-plus years. And so he and I have known each other for over 20 years now, probably 24 years now. And so it’s a long, it’s a long relationship that we’ve had, and certainly with Chris Ré, who’s the other professor at Stanford, in fact, we’ve known each other for over seven years, as well. And just being able to build that common thread of understanding and kind of how you would build companies, how you would innovate, how you deliver new products, new ideas — those are really, really important things that, you know, founders and co-founders have to share in order for you to actually have a common vision, a common destination, as the market evolves and as your company evolves.

Walter Thompson

In your mind, what sets AI product-led growth apart from traditional SaaS companies?

Rodrigo Liang

One of the really interesting things with artificial intelligence and the companies that you see today, coming into the artificial intelligence market, is that for the first time, you’re seeing products having to span a very broad market from consumer all the way into the enterprise. And so the technology for artificial intelligence is applicable broadly. And so historically, you’ve seen companies that come into the market and they do one well, but not the other. Right? You have companies like Dropbox or Zoom that you can look at, they were very focused on being able to address the rapid adoption of one of those markets.

But with AI, what you’re seeing is this challenge of having to create something that applies broadly and you really haven’t seen that since probably companies like Apple and Microsoft started creating technologies that really crossed the entire segment of the marketplace. So AI presents an interesting opportunity and challenge and, and you also see some really interesting market dynamics around margins and things like that when people kind of release products and try to figure out well, how do you create something that allows you to continue to innovate, allows you to continue to actually build value. But you can’t just do it without a commercial model that works. So I think you’re seeing a lot of that play out on the market today. And I think you’re gonna continue to see that evolve.

Walter Thompson

So, you brought up Zoom. Zoom took off during the pandemic, because it was an easy, cheap way to stay connected. It’s a pretty classic example of PLG in action. Enterprise buyers have layers of compliance and procurement for companies to navigate. So how has PLG impacted your go-to-market strategy?

Rodrigo Liang

Zoom is a great example. Prior to the pandemic, it was competing with a number of other solutions that were at least in enterprise perceived as high security, high availability, high many things right, and so for the enterprise need, and then the situation, the commercial market showed up and the situation showed up that allowed you to kind of come in and advocate for a value proposition where some of these other issues that you were dealing with was of less priority than being able to be widely available at a low enough cost. So you can deploy uniformly across the entire enterprise, right.

And so, so I think we’re seeing this as well, that you’re finding that artificial intelligence and Gen AI as a wave, it is challenging most companies in terms of their traditional policies, the traditional policies that they will otherwise adhere to, things about data security, data privacy, being able to use models that maybe you know, you you didn’t create there, there are a lot of things that companies have held for a long time, which are being challenged as a process because the value of artificial intelligence is so great, right, that you’re solving such a big problem that you have now have to revisit those constraints.

Now, SambaNova, what we’ve done is, since we’re enterprise-only, really focusing on the enterprise need, and we’ve been in this market for a long, long time, we try to mitigate those, so that companies don’t have to throw out 20, 30 years of investment in security and data privacy just to take advantage of Gen AI. So what we’ve done is created a platform that allows you to get all the benefits of the best Gen AI technologies out there, but allows you to then retain a lot of the protections that you might want for data privacy, data security, and making sure that your data does not leak inadvertently into the open domain.

Walter Thompson

Can you describe your ideal customer? And how long did it take you to triangulate your ideal customer profile?

Rodrigo Liang

Well, I think for us, you know, because we knew from the very beginning where the value proposition was going to be, it was all around mission-critical applications. And this is, by the way, and we can talk about this a little bit, but I think, as we start, having a clear identity of what problem we’re trying to solve is really important. And that’s something that my co-founders and I had very early on, which is we need to create a platform that allows enterprises to be able to deploy this in a way that you can actually feel comfortable with all the policies and processes that you already invested decades into, right. And so we came in thinking about these mission-critical applications, by the fact that you have latency sensitivities you have, you know, availability sensitivities, you have scale sensitivities, you have security, privacy, these are all standard things that it doesn’t matter whether you’re selling hardware or software, right doesn’t matter whether you’re selling SaaS or services, it doesn’t matter what product you’re selling into those environments, they all remain true, right?

They have to be scalable, they have to be available, they have to be mission-critical, they have to be secure, they have to be data private. And so we came in with a very, very strong thesis around the fact that artificial intelligence will be the dominant technology for the next 10-15 years for enterprises. And you have to solve these basic tenets of what enterprises care about. And so when we started, we effectively just focused on customers for whom those were the most true, right? That some enterprises, many enterprises will say that those things are important, but there are some enterprises, imagine a highly regulated one, you know, highly-regulated companies or highly-regulated organizations, governments and things like that, where that’s most true. That’s where we started. We started with places where, you know, our customer need was the strongest to allow us to actually be able to articulate and demonstrate the value proposition that we’re bringing.

Walter Thompson

So break it down for me a bit, your customer discovery process, how long — just roughly ballpark it? How long did that take before you were certain that you had enough information from potential customers to validate the thesis you’re talking about?

Rodrigo Liang

I think, you know, for us, and I’ll say that this is non-standard, because many things about artificial intelligence and this cycle of, of technology transition has been non-standard, right from, you know, companies like OpenAI getting 100 million users in two months to, you know, to like the new technology companies getting funded, like we raised a billion over a billion dollars in cash through the first three years of the company, there are a lot of non-standard things that many of your audience who may be have, have been in the startup ecosystem for a long time, or they’ve been in technology for a long time, they know that those aren’t things that you you perhaps witness every day, over, over a long period of time.

But in that construct, I would say that we had two classes of customer: there’s some customers that had been evaluating artificial intelligence on their own, and when we showed up, it was just so clear that they needed something, they weren’t entirely clear exactly where were all the perfect places to apply. But they were going to invest very, very aggressively. And so in those cases, which we have many customers like that, I mean, it was just a matter of a few months?

There’s kind of traditional again, this enterprise conversation, you know, just being able to demonstrate what you do, for them to understand the capabilities, bring the technical people together, so that’s frequently the way that these kind of very transformational buyers think about it: “I know I need it, I don’t have to figure specifically all the places that I’m going to use it and how to calculate the ROI and all these different individual cases, because it’s a platform I need, and I’m going to need to what’s more important for me is to get going because it’s a competitive advantage for me, right?” And that’s a big class of our customers.

There’s another wave of customers that’s basically looking at this as, “okay, how does your technology differentiate from the other offerings out there? You’ve got OpenAI and ChatGPT doing some stuff, and Google does some stuff, all these different people do their various different things? How does your technology fit into my overall hybrid solution that I wanted to plug with various different things?”

And in those cases, there’s a little bit more evaluation: “Okay, where would you fit? And if you fit in places where I have a couple options, what is your differentiation? How do I evaluate the choices?” And it’s a bit more granular in the way that they’re deciding: “Do I use A or B for particular tasks, maybe if you’re not good for B, I can use it between C and D?” So there’s, there’s a little more than that’s a little bit more like a SaaS cycle, traditional, SaaS buying cycle, but what you get out of it are customers that have a very clear idea on the value proposition to your bringing. They have a very clear understanding of how your technology compares to everybody else.

And you’re able to then lean on that to then create replicable use cases within those companies. You can say, “look, use case A looks like this, your successful use case B also looks like that, so you can be confident that we’ll be successful.” And that’s really important to be able to actually build value for customers quickly and build their own confidence that using your technology, they can get value.

Walter Thompson

When did you decide to bring on a full-time marketing person in that customer discovery journey? Was it kind of after the process you just described? Or before? Obviously money wasn’t an issue as far as bringing on marketing support, So when did that become something you pulled the trigger on?

Rodrigo Liang

Well, I think all founders will know that a big part of your job from day one is marketing. Yeah. Because all you have is some slides, right? And you have to be able to clearly articulate your value proposition to investors Day 1 and it bleeds right into articulating your value proposition to the customer. And so I think so I think, as your audience is listening to this, and probably resonates with many other founders that they have to play the role, and depending on the capabilities of the founding team. If you have it, then you don’t need to bring a dedicated person right away, because one of the people, somebody has to step into that role very, very early.

And if you don’t have somebody, which sometimes you have startups done by folks that aren’t as comfortable with the whole explaining and articulating the ideas and and the concepts in the value proposition in a way that the non-technical folks or the people that aren’t in your industry can understand — which is ultimately the job of marketing. How do you take this very domain-specific knowledge and translate it into something that is actually understandable by a much broader audience. If you don’t have that, then you have to bring it on fairly early because a big part of startups is to articulate, “why this new thing?” There’s this new thing, which is, by definition, the charge of a startup — you’re creating new things. “Why is this new thing so much better than whatever else is already out there. And whatever else I already know?”

And so having somebody that can articulate that is really important, we just happen to have I mean, we have got two incredible co-founders, professors that are so well-suited in being able to explain the technology side in a way that most people can understand. And then as part of our founding team, we had lots of people that came in with some background and being able to help articulate some of the more complex ideas around machine learning and artificial intelligence to a fairly broad base of customers, some very, very technical and some a little less technical and be able to then still convey the value proposition that we brought.

Walter Thompson

I read an interview where you said that SambaNova had “transitioned to a much more internally-led, and probably now even more customer-led, and customer-centric culture.” What led you to make that shift? Or was that always baked into the company’s recipe?

Rodrigo Liang

I think it’s always been part of the culture of the company, and harder to do early on, when you don’t have clear customers that have a clear view of exactly where they want to go with technology. And so, so I would say, in the first few years, again, we build our own chips. So we don’t use any NVIDIA chips, we build our own chips, we build all the way up to the foundation models, these trillion-parameter models that you see with GPT-4 and that class. And so for us, when we’re building that new one, we’re in that first few years of the company, when you’re building the investment stack, there’s nothing like it on the market. One, there’s nothing like it in the market, nobody knows exactly how to kind of get all that in an integrated fashion. And then, two, the people that see the value, they aren’t entirely understanding how that would fit into the rest of the ecosystem that is evolving.

You have to have a conviction around how you see your product fitting into the broader scheme of the market. As we started getting customers 1, 2, 3, by the time you get customer 20, 25, 30, now you’re starting to get a very clear point of view of exactly how the customer is going to use it. And by the way, most customers are going hybrid with artificial intelligence, nobody wants to be single-source in a single vendor, everybody wants the latitude and freedom to be able to choose who they want over a period of time they want, they don’t want lock-in. So we come in with the idea that we’ve got to win every use case with every customer and allow the customer to choose us.

Ultimately, if you start with that belief, that every deal every year, every month, every year that you go out and talk to customers, you have to win the customer again, that drives the behavior in the company of you’ve got to serve the customer’s need, versus the example of if the customer is locked in, there’s no choice. The customer’s need is maybe a little bit less important to the developers, because whatever you build, they have to buy.

Walter Thompson

It’s interesting. I mean, are you ever worried about taking on like a one-off problem, so to speak, like a problem that doesn’t really have a broad scale or scope. You’re creating a new feature for one customer that might not really scale or pay off down the road?

Rodrigo Liang

Yeah, every day, every day. We have meetings all the time about this and this is one of the hardest things, especially in a market that’s still evolving. If you look at Gen AI in the market that’s still evolving, you’re trying to figure out well, “customer A has these three classes of problems, it’s trying to solve it all through one supplier.” Maybe the right way they need to solve this is, “supplier A does problem one, supplier B does problem two,” but they haven’t arrived at that conclusion yet. Of course, as a new company, you always want to get as much of that business as you can, but what’s important is to be able to deliver that sustainably. What you don’t want to do is, say you can do it when you cannot do it.

Or you can do it, but then it’s such a big push and such a journey outside what you’re good at that it takes up all your resources delivering that. And sometimes what you end up having to do is just really break the problem down to, what is the customer ultimately trying to do? When the customer says, “Hey, can you create this model for me?” And if it’s a model that we don’t necessarily want to create or we don’t understand why they want to create, be understanding what are you trying to do? “Oh, I’m actually trying to do this task and I want Gen AI to actually produce this result.” “Oh, okay. How about this model that we do do?”

And so there are ways that you can actually really understand the ultimate problem that customers have, and try to potentially align it better with what you’re already doing, because two things happen in that case: one, your ability to deliver in a higher quality is much better because all your people are working on a focused set of things, right? You’re just gonna hit the dates better, your quality is gonna be better.

But the second thing is, you’re going to be able to then leverage that technology into the field and actually get more customers using and robustifying on your behalf and expanding the feature set on your behalf so that all your clients can benefit from that experience.

Then all your clients come in and say, “oh, it would be great if you also put in these five features.” And so you’re getting that collective feedback on a single product, versus getting all these, you know, distributed feedback on products that aren’t shared between clients. And so then everybody ends up having a subset of the feature set.

Even if you are really, really good at mapping the needs to kind of what is the main products that you have, they’ll always be cases where a very, very important customer or very, very critical need of a particular customer who creates a requirement that’s a one-off and those are individual decisions, you always have to make. It doesn’t matter if you are your three-year-old startup, or a 30-year old company, when I was at one of the largest companies on this planet, we were still making those decisions of special customers asking for this one thing, should we do it? And so I think that that scenario never goes away.

We’ll be right back after this word from our sponsors.

Are you thinking about launching an AI startup?

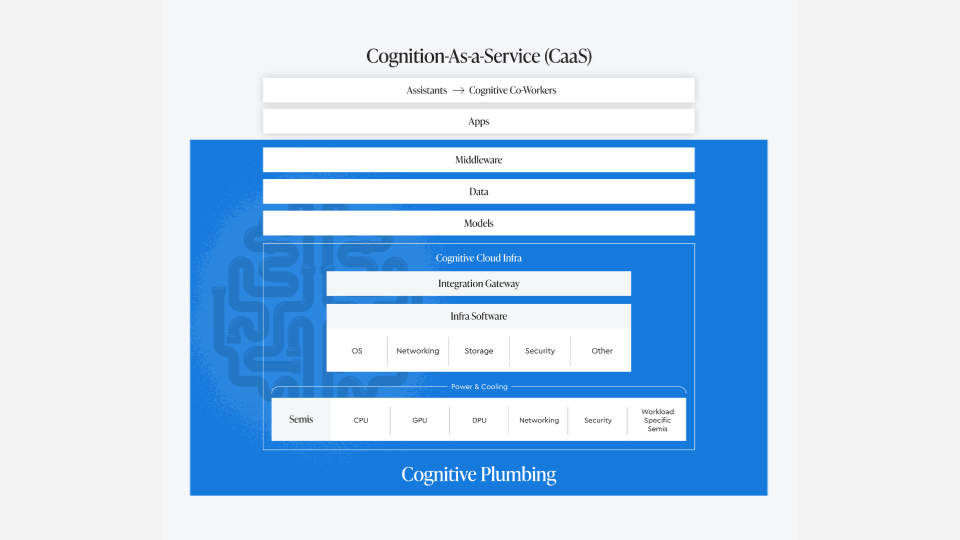

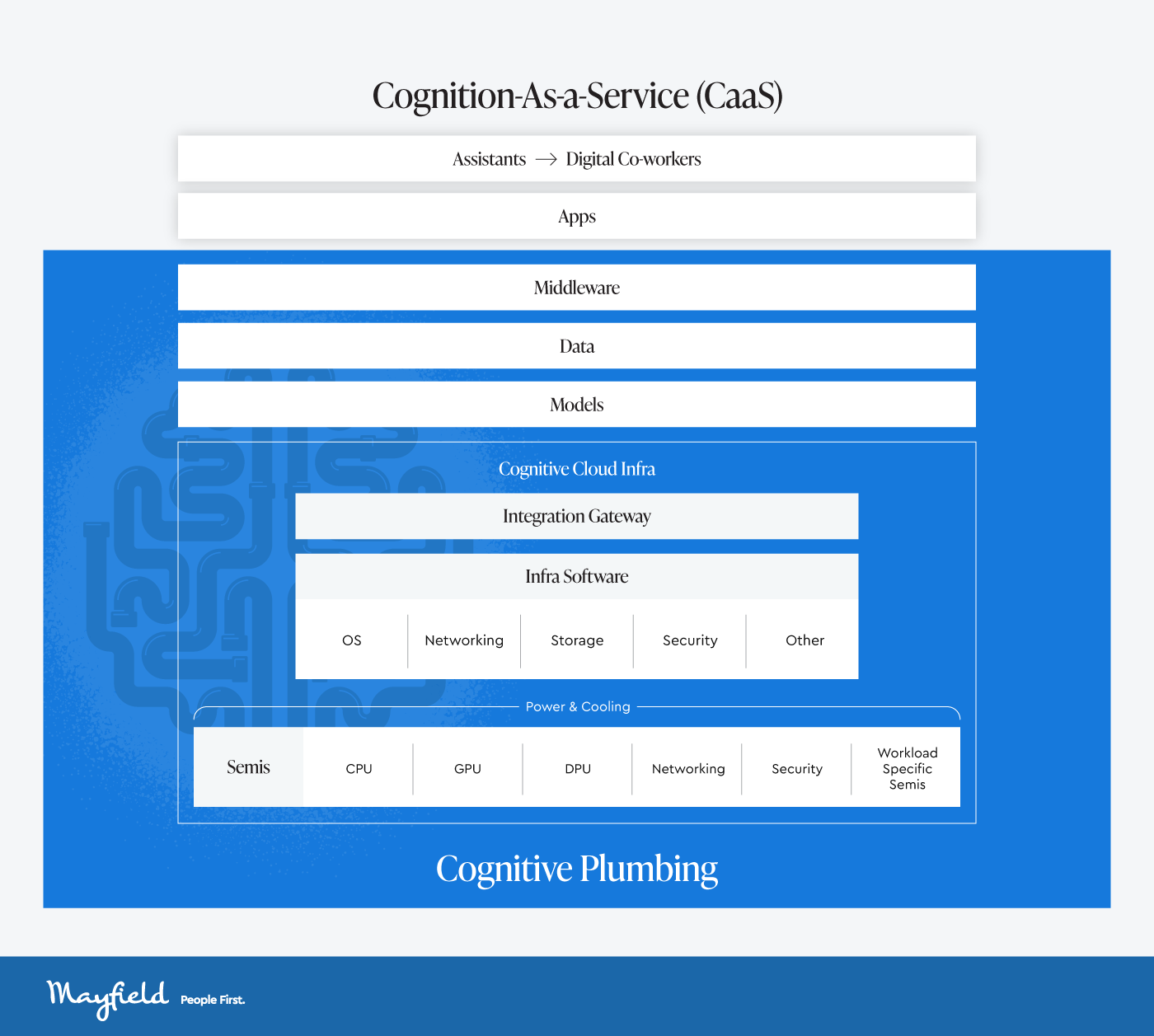

Mayfield’s $250 million AI Start seed fund is actively searching for idea-stage entrepreneurs who are working at the cognitive plumbing layer. That’s models, middleware and tools, data, infrastructure, and semiconductors/systems.

Mayfield has a long track record. Since its founding, the firm has been an early investor in more than 550 companies, which has led to 120 IPOs and over 225 mergers and acquisitions.

If you have a fundable idea for an AI-first startup, email aistart@mayfield.com.

Every business that incorporates AI has to account for data privacy, compliance and governance.

That’s why Securiti developed its Data Command Center. Instead of setting up different tools that can eat up time, money, and add complexity, Securiti’s award-winning technology: automates compliance with global privacy regulations; includes a library with more than a thousand integrations across data systems, and identifies data risk to enable protection and control. To learn more, visit Securiti.ai.

Now, back to my conversation with Rodrigo Liang.

Walter Thompson

A B2B SaaS startup might share their product roadmap with an early customer to get buy-in. You’re one of the best-funded AI startups in the game. Is that something you can afford to do? How transparent are you with customers as far as, “here’s what we’re thinking of, or here’s what we’re working on.”

Rodrigo Liang

Again, our stack includes chips through servers, through a variety of things around what we call the AI operating system, right? If you think about how these models all have to interact with each other, and interact securely, and privately, all those things will kind of generally name it in the category of AI OS, just being able to have many, many models, operating concurrently on the platform. So if you think about all those features, that to us, our unique advantages, we tend to be able to give them directionally what we’re doing, but not the specific features, just because these are things that competitively are important for us to make sure that we’re able to drive differentiation and ultimately deliver as well.

As you get up into the use cases, we’re actually quite transparent. Today, we build our trillion-parameter mall models off oftll the most popular open source and we tell them “okay, we’re using Llama 2, we use Mistral, these are all the types of models we use. And the next wave, we’re going to use these models, these models, these models, these are the configurations of the models, these are the sequence length, these are the batch sizes, the vocabulary sizes, we’re very transparent about what we do as far as kind of how we do these large, large models, and then how those models then are then translated into AI business tasks that you can take advantage of.

Because you’re working on business features and tasks that you don’t care about, then what am I doing? So we’re very, very direct about saying, “look, here’s your call center support, here’s the code Gen support. Here’s your legal assistant, here’s summarization, here’s your named entity extraction.” It will give you all the very specific things that we’re supporting, so that they can come back and tell them “Yeah, I don’t know, I’m not using those things, but I care about that.” And so we’re able to then, using feedback, adjust what we support more of, because it is all about making sure that the customers when they get a platform, they get ultimately what they need to accelerate delivering value into the corporation.

Walter Thompson

Interesting. What challenges are you seeing with regard to AI adoption, and how would you advise a smaller startup that’s trying to get buy-in with C level executives? My sense is this is something you do over time by building relationships, but how do you get that ball rolling initially?

Rodrigo Liang

A lot of it is a function of the timing of the market as well. When we started the company back in 2017, there wasn’t a very great understanding in the commercial enterprise of what AI could do for us. It took ChatGPT showing up for a lot of people to really, for the first time in a very hands-on way, get a sense of, “oh, I see what Gen AI is all about.” And so I think it depends on the market. Now, as you kind of move forward from here, I think there’s a lot early education that’s taken place, and I think a lot of the enterprises are starting to realize, “okay, in the flow of work for for AI, there are things that I can get from these vendors and the suppliers that exist, you know, SambaNova or NVIDIA or OpenAI, there are places that are delivering these technologies into the enterprise. And there are things that I’m not exactly sure how I could solve. And I think that customers are starting to get that level of insight into what can I do for them?

I think that having that very, very active conversation with customers, a broad range of customers, they don’t even have to be customers today. But our mentality is one where everybody we talk to will one day be our customer. Right? It might be tomorrow, it might be five years from now, but one day, right? And so if the mentality is one where you’re trying to find out what are they thinking about and how could we potentially solve it? I think it actually starts opening a lot of doors for people to say, “okay, well do we have something to my favorite problem and a gap, something that might exist?” So that’s kind of a very just — is there a product-market fit with a need that you might have?

I think the other aspect for new companies that are trying to enter the market and trends we talk about is, look: another thing that’s interesting about AI is the cost of actually validating your technology now is extremely high, extremely high, right, you look at the cost of running these GPU cycles on the cloud. I mean, a lot of companies are trying to offset that by raising hundreds of millions of dollars in venture funding, right, but not everybody can do that. And so you kind of have to think about effective ways that maybe you can partner with folks, partner with other companies to leverage kind of the relationships that they might have and leverage some of the technology and tools they might have to kind of prove out some of the things that otherwise you have to do all on your own.

We’ve been very open about the partnerships we have with companies like Accenture, with the US government, with other startups, that is a very, very important way that you can actually engage your technology with others and in some ways actually get fast feedback on how well that technology actually solves a particular type of problem. Those types of interactions that allow you to shorten the cycle, allow you to actually prove it faster, allow you to actually make sure that you connect to a problem that people are actually struggling to figure out how to solve, right, those are very, very important before we even get to that commercial conversation that we have to find a procurement person inside that company. Solving a problem is much more expensive these days than it was before, just because of the cost of the computation. But still, the process of solving the problem and process of making sure that you have value in your tech, finding a very efficient way to do that before you enter the procurement process is really, really important.

Walter Thompson

For product-led growth to work, you really need to build consensus and alignment within the entire organization. A lot of companies don’t have that much in-house expertise. Has that been a challenge for you? Or is or is just kind of, “game on, as far as we want generative AI? How can we get it?”

Rodrigo Liang

No, it’s absolutely true. I think intersecting the customer will, wherever they are in their journey, obviously, of companies that are incredibly savvy in AI, they’ve been doing artificial intelligence for a long, long time, they have thousands of people in there. And so you have companies like that. And there’s some companies that are just getting started in their journey, they maybe just hired the first couple of people to really look at it.

And so understanding where customers are under journey, figure out kind of what you can offer for each of those types of customers at those stages. SambaNova, because we’re a full-stack company, we can go from chips all the way to models, the reason we took it all the way to the highest level of abstraction was we wanted enterprise customers to have an interface that looked like ChatGPT. If you look like ChatGPT for the open market, I can give you the private version of that. It takes a lot of investment to take your technology stack all the way up to that level of abstraction. But what it did for us was, it opened up a whole class of customers that otherwise if we’re down below where we’re actually teaching you how to program our chip, there was no chance that they would actually have enough expertise to be able to do it.

Now certainly, we have a large number of customers with that level of staffing for artificial intelligence that are able to come in and say “I want to create my own model on your hardware, and I’m going to just do it ourselves.” Certainly we have loads, but being able to then manage out your customer base and be able to map the offering you have to their lifecycle into where they are in the journey itself, I think is really, really important to actually be successful in this market.

Walter Thompson

How does your PLG approach enhance the customer experience in a way that encourages people to become advocates or evangelists?

Rodrigo Liang

We really are focused on getting quick proofs of success.So we have these things that we show a customer called previews and what the previews are is basically, if you think about use cases for AI, a lot of people look at, “oh, I see this model on the web — GPT this, GPT-4, GPT-3.5, I see Mistral.” Those are not use cases for the customer. Those are amazing models that ultimately integrated into a workflow that will deliver end benefit to the customer. And so what we’ve done is, we’ve created these previews, and these are business outcome previews, “how do I take the technology that we have, but instead of showcasing how much better technology is compared to somebody else’s technology, let me show you how this technology feeds into a solution that is important to your business, right? How do I create value for you and deliver something you can’t get from anywhere else to give you a sense of how quickly you can take this technology stack and actually create benefits into your business?”

And that’s an incredibly important way to actually create acceleration, because otherwise, you leave it to your customer to figure out how the heck do I actually show value? And we want to actually make sure that the customers can show value very, very quickly.

Walter Thompson

Last few minutes of our interview here, but if you could share some advice for people who are starting out or who are thinking about starting out with an AI startup. You mentioned, pretty clearly, SambaBova has raised more than a billion dollars in its first three years. Do you have any general advice for early-stage AI founders who are trying to raise a seed round right now in 2024?

Rodrigo Liang

Two things: it’s much better to be raising now than it was last year, right? So your timing is much better, I would say, the understanding in the market and investor community around what AI can do, and what all the possible things that add value, I think is significantly higher than it was say, three, four years ago. And so I think be very, very clear about the value proposition that you bring, just having a tech that does X, Y, Z. Imagine these investors are seeing this probably, you know, 20, 30, 40 times a day and so there are a lot of ideas out there, and many of them aren’t going to be able to actually deliver value into the customer base.

Think about something that is of significant value and think of something that is of significant value over a protracted duration of time, not as only valuable today, but you can see how it accretes value over time and allows investors to actually buy you time so that you can actually deliver more and more traction in the marketplace. Right. And so those are the two important things that I can think of.

Walter Thompson

I think a number of my listeners are likely people who have an engineering or an academic background, if they’re, they’re thinking about starting up. But becoming a CEO kind of takes an entrepreneurial mindset. So was this a challenge for you way back when you did your first startup, and do you have any advice for helping someone overcome this hurdle? It’s just a mental hurdle, but it’s real.

Rodrigo Liang

Some people will say this is still a challenge today. Every day is a challenge, you know, the role of and it’s not just a CEO, but the role of leaders in a startup. The startup needs what they need from you changes year after year, and you have to sit down and figure out what it is that the company needs from you.

That was never my case, because we just had such an amazing technical team that could deliver on the technology that I didn’t have to be that person. But for many of your audience, you might be, you might be the technical guru for the company. And so there’s a stage where what the company needs you you figure out is to solve that hard problem, right, solve that really hard problem. And many, many startups in the early stages are formed because you have an incredibly amazing technical solution driven by your own capabilities. And as we grow, then the company’s needs start changing, because the hard problems have been solved. Now, it’s all about scaling, robustifying, creating all sorts of other things. And yet, what the company needs next for you to take this incredibly sophisticated, amazing technology and explain it to somebody, to a layman in a way that they can understand value.

Now, suddenly, you became a marketing person, right? And so that’s it: the needs of the company change, change what you have to do very, very quickly, and our ability to go from fundraising, to explaining the value proposition to customers, to helping customers actually incorporate into your change management, all of those things, those end up adding skills that we sometimes have from before, but oftentimes did not. And so I would say, for entrepreneurs, if you want to become an entrepreneur, lead a startup, be very, very adaptive, be very open to learning new skills, that you’re not going to do them perfectly. But the company needs you to do some of it.

Walter Thompson

How would you advise someone who’s looking for a job with an AI startup? What should their due diligence process look like and what are some questions that you would ask during the interview process?

If you’re sitting across the table, like you want a job with an AI startup, what are some of the questions you’d be asking them to kind of figure out like, you know, “is this a job worth taking? Is this a bet I want I want to make?”

Rodrigo Liang

Yeah, okay. Yeah. So same, same question: “why did you decide to tackle this problem?”Try to try to align that with what you’re interested in? Why, why did they do it? Right. And the [answer] is, “I wanted to just make some money,” that’s not a great answer, right? There’s lots of ways to actually create companies that add value. And can you can do that, and frankly, you know, startups. You go in for many, many other reasons than that. So find something where your passions, your interests, your wellness, technical, or often a few perspectives match what they want to do, right? I think that that is really important, because near the journey of a startup is a lot of ups and downs, and incredibly exciting, incredibly exciting, but you got to the same page as the mission of the company.

I think beyond that, the very, very next question that I would ask is, “why is it long-term viable? Why is this technology, whatever you’re building, long-term viable.” It’s an incredible competitive environment. The environment that companies big and small are tackling, it is not just the small players. I sometimes use the phrase, it’s a stampede of the largest creatures in the world. And you know, if you’re sort of in the middle of it, you’re scurrying around, right? And so you have to understand it’s a competitive environment. So you have to believe that there’s a moat in the technology that allows you to be able to differentiate, and differentiate not today, but for a long, long time.

And then finally, I mean, with startups, you’ve got to have money, right? It’s a very expensive endeavor, especially today with the costs of actual building these things. So “what is your cash position, and how do you intend to fund your venture all the way until you’re profitable?” These are somewhat pragmatic questions, but it’s a reality that it’s a competitive environment and having cash is going to be very important.

Walter Thompson

So if I’m interviewing at an AI startup today in 2024, how many months of runway do you think they should have for me to say “yes, I’m willing to get on board a year, year and a half, two years.”

Rodrigo Liang

The way I think about that is if you’ve got to match it to the milestones that you have, and different companies have different strategies, and it’s probably a subject for a whole other podcast around how fundraising works. But I always advise folks that you don’t have to raise funds right away, but it’s always better to have more than enough, right? That’s step one, right? It’s always better to have more than enough. But the second one is to make sure that you have a clear idea of what those milestones are that you think will drive value. Right?

If the next big milestone for your company is three months away, well, you should have money for six months. If that next milestone is a year away, maybe you need significantly more than a year, you know, I mean, like, you want to be able to actually have cash until that big milestone because those milestones drive confidence in the investor base that your technology is actually producing value. But these things are imperfect, right? The market is changing, you might have some surprises, and so you want to make sure that the cash covers the next big step in your milestone — step function milestone — in order for you to get to that.

The worst thing would be — this is kind of the tragedy I see sometimes — the worst thing is when you run out of money just before that big milestone, right. So you never want to be in that situation. You always want to be in a situation where the cash covers you past that major milestone, and make sure that when you raise, you raise enough money to cover the next milestone after that,

Walter Thompson

Rodrigo, thank you very much for your time. This has been a great conversation. I appreciate it.

Rodrigo Liang

Thanks for having me.

Walter Thompson

I’ll be right back with some show notes after a word from my sponsors.

Fund/Build/Scale is sponsored by Mayfield. If you have a fundable idea for an AI-first startup at the cognitive plumbing layer, email aistart@mayfield.com.

The podcast is also sponsored by Securiti, pioneer of the Data Command Center, a centralized platform that enables the safe use of data and GenAI. To learn more, visit Securiti.ai

Thanks again to my guest, Rodrigo Liang of SambaNova, for appearing on the podcast.

Coming up next: an interview with Ozzy Johnson, Director of Solutions Engineering at NVIDIA.

Ozzy and I talked about where early-stage AI founders need the most help, how people from academic/research backgrounds can more easily shift to an entrepreneurial mindset and we also spent some time exploring strategies for nurturing a successful AI developer community.

He also shared some thoughts about balancing initial spending with the need to drive early growth and which traits successful AI founders have in common. (Spoiler: they aren’t all developers.)

If you’ve listened this far, I hope you got something out of the conversation. Subscribe to Fund/Build/Scale so you’ll automatically get future episodes — and consider leaving a review.

For now, you can find the Fund/Build/Scale newsletter on Substack.

The Fund/Build/Scale theme was written and performed by Michael Tritter and Carlos Chairez. Michael also edited the podcast and provided additional music.

Thanks very much for listening.