The idea for Brighter came to Jake Winebaum during a dinner conversation with his wife’s parents in 2010. After hearing his father-in-law talk about his frustration with the high cost of his recent dental work, Winebaum started thinking about ways he could use technology and consumerism to help patients get control of their health care costs and better navigate the healthcare system.

Healthcare Gets a Check Up

With a little bit of research, Winebaum discovered that, 50 percent of the US population didn’t have any kind of dental insurance. Compared to only 11 percent of the US population that didn’t have medical insurance.

Consumers, says Winebaum, were paying for a huge share of their dental care out-of-pocket but without any visibility into costs and quality and without any negotiating leverage. “Can you imagine?” he asks. “Here’s a huge, $140 billion industry where the consumer is spending $70-80 billion dollars out of their own wallets and nobody is helping them get better value.”

And that’s when the seeds of the idea behind Brighter began to grow. “The business of healthcare cried out for a transparent marketplace for the purchase of the care itself,” says Winebaum.

An Initial Prescription

When Winebaum first approached Navin Chaddha at Mayfield, the concept of Brighter was just a few PowerPoint slides. “All we had was a basic idea of how a healthcare marketplace platform would work in seamlessly connecting the patients and providers,” says Winebaum.

But that was enough. Mayfield could tell Winebaum was onto something important. “They got it right away,” he says. “The market was big and they immediately saw the opportunity of our venture. And I got their people-first philosophy, Mayfield’s confidence in me and my plan. Even though we hadn’t ironed out the details yet, they wanted to be involved.”

Patients First

Winebaum founded Medical and Dental Commerce Corporation. Mayfield funded the seed round along with Winebaum. Like Amazon’s initial focus on books, the company picked dental for its first marketplace because dental had several unique characteristics that made it the ideal test bed for technology and consumerism in healthcare: a highly fragmented population of 190,000 privately owned dental practices, the high per-capita out-of-pocket patient spending, and the completely opaque but highly variable pricing of dental procedures. They felt it was the ideal initial vertical for the first healthcare marketplace.

“The first thing we did was to do what insurance companies did,” he says. “We went out and negotiated group discounts on behalf of our prospective members.

“We were able to do that and generate a very powerful value proposition for uninsured patients. In addition, we proffered a good value proposition for the providers who would be able to attract new patients without having to spend additional money in the complicated world of online marketing.”

The Challenge of Prevention

“Our proudest accomplishment was when we launched the Brighter dental marketplace, creating a very easy-to-use but powerful member and provider experience,” says Winebaum. “We were able to tame a complicated system and come to market without a hitch to provide members and providers with the kind of digital experience that they have become accustomed to in every other aspect of their lives.”

Patients loved Brighter. For the first time, they had the ability to take control of their healthcare experience and costs. Winebaum was pleased to discover that his platform was also popular with providers. “We delivered new patients to their practices who had made an informed decision on price and quality in selecting that provider,” he says.

However, Brighter faced a big challenge. Because of the hyper-local nature of dental care and the infrequency of dental visits by uninsured patients, it was very expensive to reach patients at their time of need.

“People who don’t have dental insurance tend not to go the dentist as regularly for preventive care,” says Winebaum. “Many went to the dentist when they had a serious dental problem. And getting in front of them through marketing efforts at the right moment proved prohibitively expensive.”

Assuming Risk — Series B

The problem was clear: “How could we aggregate patient demand on our platform,” asks Winebaum, “without having to market to individual patients?”

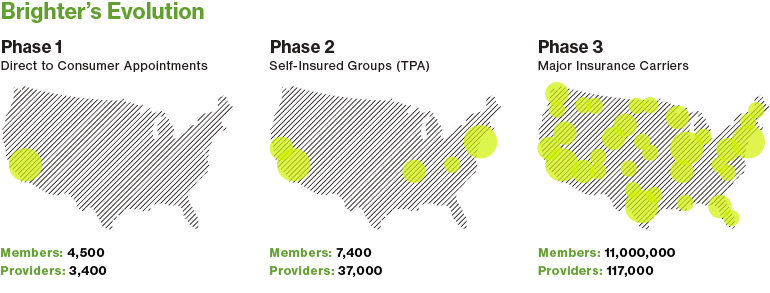

The answer was to serve self-insured employers as the third-party administrator of their dental insurance plans and that was the segue into the second phase of the company. Using the dentist network, core platform, and marketplace that they had built for individuals, Winebaum and his group were able to save money for companies and their employees while providing them with a truly modern, digital health insurance experience.

“Almost immediately,” he says, “we were able to reduce claim costs and improve patient satisfaction as well as actively engage providers in a healthcare marketplace.” As a result of this success, Brighter was able to deliver a larger pool of patients to providers and increase liquidity in the marketplace.

“We were able to tame a complicated system and come to market without a hitch to provide members and providers with the kind of digital experience that they have become accustomed to in every other aspect of their lives.”

Moving Up the Food Chain — Series C

The next phase for Brighter brought them to the top of the healthcare food chain.

“As we started to work with large, name-brand employers, we quickly caught the attention of the large insurance companies,” says Winebaum. “We were winning away their customers and delivering a very different kind of dental benefit experience. We were helping employers and their employees reduce their dental care costs and, at the same time, providing higher satisfaction.”

This led to the next level of Brighter’s evolution: the ability to help larger health industry carriers provide the same kind of experience to their customers.

“That’s what made us valuable to the larger carriers,” says Winebaum. “Historically, the insurance companies didn’t have a personal connection to their members, particularly in the digital realm. Their web and mobile offerings were not used by their customers, largely because they didn’t yet offer the kind of consumer digital experience that added convenience, control, and transparency. They were basically B2B companies that sold insurance plans to larger employers and outside of the claims process (the dreaded EOBs, explanation of benefits mailings), had little interactions with patients.”

Brighter didn’t merely provide a theoretical way of doing business. It knew what it was doing. At this point, it had five years of experience and understood how to engage individual providers and patients in a way larger insurance companies hadn’t yet figured out.

Patience and Persistence Pays Off — Series D

With multi-million dollar contracts and successful implementations with the largest dental carries, Brighter was well on its way to success. Brighter initiated its Series D financing in early 2016. Unfortunately, the timing wasn’t ideal. VCs were starting to tighten the purse strings and cutback on investments outside of their portfolio companies.

“I went to my board with a list of 15 venture capital firms that I didn’t have a relationship with that I needed help from my board in contacting,” says Winebaum. “Navin at Mayfield signed up for 12 of the 15 introductions, and within 24 hours I had appointments with 10 of them.” Brighter closed the round quickly at a solid valuation, putting the company on solid financial footing as it moved toward the future.

“Jake Winebaum is a successful serial entrepreneur who likes to solve big problems. When he decided to focus on the under-served $140 billion dental market in 2010, we knew he would create an innovative, mission-driven healthcare company that would make a big impact. Today Brighter is the industry’s leading dental insurance marketplace.”

— Navin Chaddha, Mayfield

The Future Gets Brighter

“When we started 6 years ago,” says Winebaum, “the concept of using technology and consumerism to turn passive healthcare patients into healthcare consumers was just starting to percolate. Now, with healthcare costs continuing to rise out of control, transparency and digital engagement are widely acknowledged as the key to managing costs down. We were very early with our healthcare marketplace, but thanks to Mayfield and their patience and consistent support, we have turned that initial concept into an industry-leading platform and business.”