BioNTech’s founding story dates back to the late 1990s, when CEO and co-founder Uğur Şahin, his wife and co-founder Özlem Türeci, and the rest of the seven-person founding team began their research.

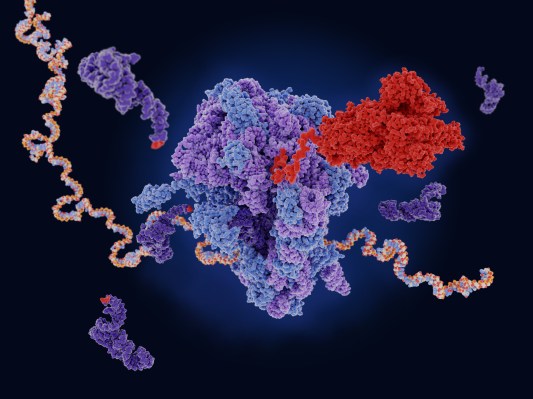

Focused specifically on an area dubbed “New Technologies,” mRNA stood out as one area with tremendous potential to deliver the team’s ultimate goal: Developing treatments personalized to an individual and their specific ailments, rather than the traditional approach of finding a solution that happens to work generally at the population level.

Şahin, along with Mayfield venture partner Ursheet Parikh, joined us at TechCrunch Disrupt 2021 to discuss the COVID-19 vaccine, his long journey as a founder, what it takes to build a biotech platform company, and what’s coming next from BioNTech and the technologies it’s developing to help prevent other outbreaks and treat today’s deadliest diseases.

“At that time, mRNA was not potent enough,” Şahin recalled. “It was just a weak molecule. But the idea was great, so we invested many years in an academic setting to improve that. And in 2006, we realized ‘Wow, this is now working. Okay, it’s time to initiate a company.'”

While it was time to bring the work out of the lab and into a formal company setting, Şahin explained that it still wasn’t the right time to seek out traditional venture funding. The team recognized that there was a lot of work to be done before they had anything ready to take to market.

“It was very clear that this will not be a home run,” he said. “It would take a further eight, nine years until this is a particularly mature product, and we wanted to start a company with just us as founders, and somehow get funding without getting investors into that.”

To achieve that delicate balance, Şahin and his co-founders looked to non-traditional sources, including the Strüngmann family (two BioNTech founders are members). Building on a relationship that began with an investment in Ganymed Pharmaceuticals, Şahin’s first startup which he co-founded in 2001 with Türeci and Christoph Huber, BioNTech was able to get the runway it needed without the usual expectations of periodic proof of market traction.

“They [the Strüngmanns] asked us, ‘Do you have anything else?,’ and we said, ‘Yes, we are working on new technologies, but this is not suitable for classical investments,'” Şahin recalled. “They said, ‘Let’s check this out anyway,’ and we shared [BioNTech’s work], and they were fascinated.”

The Strüngmanns were willing to be patient and allow the technology to develop at the right pace, so BioNTech was able to get running with the right initial financing infrastructure and timeline expectations that it needed to deliver a mature, safe and scalable product.

BioNTech kept mostly out of the public eye until around 2013, when it began making its first deals and partnerships, including a collaboration with Genentech. These were seen by the broader community as validation of the work it had done on the tech stack, Şahin said, which led to more partnerships, as well as a Series A financing with more traditional investors, and eventually, a public market debut in 2019.

BioNTech’s journey obviously required a tremendous degree of commitment to the mission, as well as grit, determination and perseverance on the part of Şahin and his founding team. Mayfield’s Parikh, based on his experience with biotech and deep tech portfolio companies, talked about the unique challenges faced by founders with scientific backgrounds and what it takes to build successful companies.

“A lot of scientist founders have not been CEOs before,” Parikh said. “They have gotten a product to market, but not scaled revenues and business. So you have to be this amazing continuous learner, who also has very high EQ and can form deep trust relationships [ … ] Becoming a CEO is a full-time job in itself. The first task of a scientific founder CEO is to find a scientific co-founder who’s better, ideally — not equally good, but better at the science — so that they progress, right? Otherwise, that trade off just feels so hard, and so difficult to make.”

What makes it easier, or at least more manageable, is keeping a clear focus on the mission. Şahin says that BioNTech remained focused on that vision throughout their development as a company, despite unpredictable twists in terms of what its pursuit looks like in practice due to major global events like COVID-19.

The company happened to be positioned extremely well to use its mRNA technology to address the novel coronavirus, in part because it already had a partnership in place with Pfizer to develop a flu inoculation. But Şahin stresses that the broader vision remains bigger than developing other vaccines and extends beyond the use of mRNA specifically.

“You can just continue to ask the question: What are the weaknesses of certain technologies?” Şahin explained. “For example, antibodies are great molecules, but making bispecific antibodies [antibodies that can bind simultaneously to two different types of antigen] is difficult. So we developed the technology to make mRNA-encoded bispecific antibodies, which dramatically reduces time to clinic and circumvents a number of problems associated with bipecific enterprise.”

Ultimately, BioNTech’s mission is to make treatments that are optimized not only to specific patient needs, but also to time and place. All the treatments in the company’s pipeline are about refining the approach to addressing disease, making the process much more like a metaphorical scalpel than a bludgeon.

“We can develop classical pharmaceuticals like a vaccine here [in the case of COVID], but on the other side, also really continue to follow our vision,” Şahin said.

“What we want to accomplish is [ … ] to provide the patient the best possible treatment based on our extra knowledge of the planet at that time [ … ] Information is now so fast-changing, so we are talking, for example, about adapting our vaccine to COVID-19 variants. But the same can be considered for adapting a vaccine of a cancer patient toward a changing tumor. So it’s technically the same step, and so that means regardless of what we do here, we can apply the principles to treating patients, and that’s an exciting prospect.”