What’s the key to start-up success? Sell first.

That’s the philosophy that Murli Thirumale and Gou Rao have used to create three successful start-ups. The most recent is Portworx, which was acquired by Pure Storage for $370 million in September.

Rather than immediately investing in engineering or preparing decks for potential investors, they first find customers willing to help them hone a basic idea into technologies customers will actually buy. “People don’t have time to waste on things that don’t solve their problems,” says Thirumale. “This way, you have partners that want you to succeed, because you’ve solved their problem together.”

This sell-first idea is core to what they call SDBS, a formula that stands for sell, design, build and scale. Thirumale developed the approach when he was building enterprise networking businesses inside Hewlett-Packard in the 1990s, in part by partnering closely with chipmaker Qualcomm. He met Rao, an OS architect at Intel, through family friends in 1999. Within months they’d quit their jobs to create Net6, which made secure networking solutions for the burgeoning Voice-over-IP market.

After selling Net6 to Citrix in 2004, the duo ran the same play to create Ocarina Networks in 2006. Working with potential customers, they came up with storage optimization software that allowed companies to store up to ten times more data on traditional enterprise storage systems. In 2010, Ocarina was acquired by Dell.

By 2013, Thirumale, Rao and Vinod Jayaraman, who had joined Ocarina in 2008 as principal architect, were ready to start something new. As with both previous companies, they considered a broad range of ideas.

They could catch the fast-growing AI wave by creating a data visualization platform so even non-data scientists could ask and get answers to complex questions. Thirumale, in particular, was excited about creating a smart ring platform that would let consumers control their TVs, thermostats and car doors with air gestures. Or they could stay in storage and come up with a new approach to match the way many enterprise software developers were starting to create and deploy their code: within virtualized containers, such as those managed with Google’s popular Kubernetes framework.

“We took our time to do due diligence in all three areas, to make sure we could find a problem worth solving, and one we could really get excited about,” says Rao.

Their process doesn’t just involve whiteboard discussions and PowerPoints, but building an intentionally “half-baked” prototype, says Rao. It doesn’t have to be even as ambitious as a minimum viable product, often mentioned as a mandatory early step. But it does need to give customers a sense of how the technology would fit into their lives.

“If we were to build a car, we wouldn’t start with the engine but with the seats, so the customer would know how it would feel to sit inside,” he says.

Typically, this means focusing on the user interface more than technical features and capabilities. In the case of the smart ring, the prototype progressed to the point that Jayaraman, wearing a circuit-card on his wrist, was able to show how he could navigate through Google Earth using only hand movements.

“We’re big believers in designing the UI first, and saving the hard stuff for later,” says Rao. “It’s a lot easier to get off on the right path, and then make micro-corrections.”

The key ingredient: customers

Of course, key to SDBS is finding customers willing to take the time to help define a winning product or service. Portworx’s founders called upon customers from their previous startups, and also hired industry consultants, which provided additional potential customers willing to hear a pitch.

But they also hired veteran enterprise technology salespeople of their own—a major investment, especially since the company was nowhere close to landing significant contracts. “We hired Paul Searles and Jake Johnson in 2016, nine months before we planned on having a sellable product,” says Rao. Rather than sales, their quotas were tied to metrics such as proof-of-concept starts or the number of demos they gave to qualified leads.

“It’s about finding co-development partners,” says Thirumale. “From our perspective, they are angel investors of a different sort.”

Often, these partners fell into one of two groups. Either they were innovation leaders themselves, and wanted to partner with a vendor who could help them get a competitive advantage by pioneering the use of an important new technology. Or the Portworx team convinced the partner they were uniquely qualified to solve its storage related problem. “If they realize you’re going to move mountains to make them successful, it’s like they’re getting some of the best folks in the world to work for them for free or for a big discount,” says Thirumale.

Building Portworx

Ultimately, Thirumale, Rao and Jayaraman chose to stick with storage. The AI market was already getting crowded, and after deep analysis they realized creating the smart-ring platform would require taking on cable-box makers—not a business they were interested in.

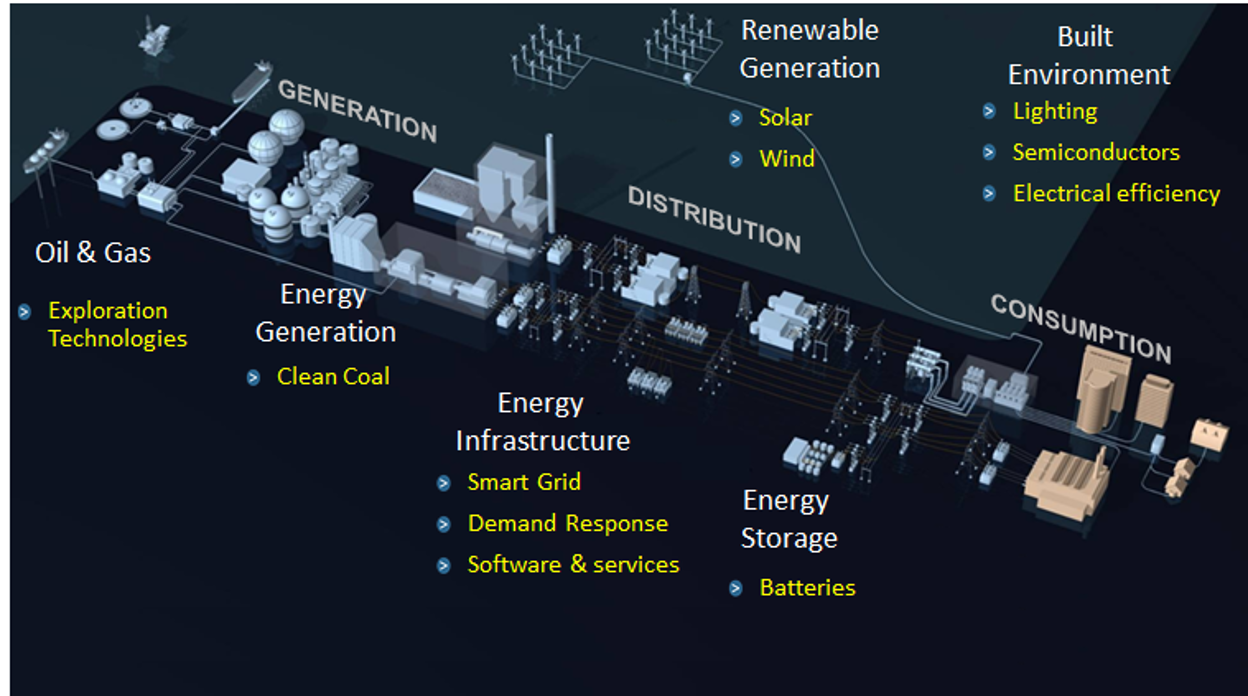

Plus, storage was ripe for change. Plenty of startups had created “cloud storage” solutions that were geared for the traditional buyers of such gear, data center storage administrators who were driven heavily by the desire to reduce the amount of hardware they needed to buy.

Rao, as chief technology officer of data protection during his years at Dell, saw a more strategic opportunity: application developers, who were flocking to containers that let them create and run apps that took fuller advantage of the cloud, such as the ability to quickly add new features, or to secure them from the latest cyber-threats. But there was no way for developers to use storage to the utmost benefit—say, by enabling apps to continually decide whether time-sensitive data should be stored in a cloud data center in Oregon or Ireland.

“We knew that anytime there’s such a major shift in how enterprises manage their applications, the infrastructure needs to be re-thought,” says Rao.

Mayfield managing director Navin Chaddha helped the team think through the implications of the shift, Rao recalls. “Are you part of the storage ecosystem, or part of the software ecosystem?,” he asked the Portworx founders at an early board meeting. Rather than hedge, the team went all in on software.

Working with Mayfield: One mark of a great founding investor: knowing what not to ask

Read more >>

As with most entrepreneurial success stories, the timing was perfect. Developers were adopting the open-source Kubernetes platform, originally created by Google, for managing container-based development. Rather than try to convince customers to adopt something entirely new, Portworx created its platform around many of the processes and the vocabulary of Kubernetes.

Before long, sales had ballooned to more than 100 customers, including Comcast, GE and Lufthansa.

While the company leveraged open source technology, it did not embrace open source as a business model. Rather than give away its technology for free and charge for added features or customer support, Thirumale chose to forgo contributions of code from thousands of open source developers. “Maybe we’re old-fashioned, but we believe we can do the job with 40 or so very bright, hand-picked people,” says Thirumale.

He cites a fundamental reason why there are so few financially successful open source companies: because they’re not focused on winning over the people with the money to spend. “You can get a lot of people to join your community, in part because they wrote code for it. But often, these people don’t even work for large enterprises. They can deliver mind share, but not wallet share.

While agreeing on what Portworx should do was challenging, the decision to sell to Pure was far less taxing. Having executed so well on the product front, the main challenge ahead was to address the final S in SDBS, which stands for scaling. “That is traditionally the most expensive phase, because selling is expensive,” says Thirumale. “It became clear to us that Pure could rapidly accelerate our ability to achieve our mission. It was like strapping a large Go-To-Market rocket to ourselves.”

A broader point of view

Their experience founding three startups has reinforced for Thirumale and Rao that success is never a straight line. “Starting companies is always a roller coaster, and anyone who tells you they had it all planned out is lying,” says Thirumale. “So you need partners who you never need to worry about, because you know they’re in for the whole ride. I knew that with our first company, when we pivoted three times and built three completely different product lines—and nobody even brought up the idea of giving up.”

Most of all, it’s given them conviction in their approach of working with customers early in the process and relying on feedback from these potential users to guide the product development process. “The popular image of the entrepreneur is that there’s a flash of brilliance and lightning strikes and you have your idea,” says Thirumale. “But customers don’t buy brilliant ideas. They buy solutions that solve a problem for them.”