Silicon Catalyst recently hosted their spring 2023 Portfolio Company Update, where Mayfield Managing Partner Navin Chaddha shared his insights on the semiconductor industry, company building, generative AI and more in conversation with Dave French. Key takeaways include:

- In order to win, startups need to first get mind share with their potential customers, then they need to get market share, which will lead to revenue;

- As venture capitalists, we aim to partner with great people because ideas and markets will come and go, and great people will pivot to find the right opportunity;

- The plateauing of Moore’s law has led to the need for application-specific architectures and the renaissance of silicon;

- Silicon is not the only deeptech opportunity – entrepreneurs should also look at innovation in physics, chemistry, biology and other sciences;

- AI is a real trend but it won’t happen overnight, so founders and investors should be patient.

The full transcript is available below – we’re proud to be partnered with the Silicon Catalyst team to help nurture the semiconductor entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Dave:

It’s an honor to be at a major Silicon Catalyst event, probably the biggest event of all time for this group, and it’s also an honor to be able to speak with Navin, who’s a legend in our industry, and in other industries as one of the best investors in early stage activity throughout many segments, and so, I’m pleased to be here.

My goal here is to allow Navin to impart the maximum amount of wisdom to this group of highly intelligent people in 31 minutes.

Navin:

I think it’s going to be the other way. There’s so much wisdom in the room, right? At the end, crowds win, not individuals. Really looking forward to it, and thank you for your kind words.

Dave:

So we’re going to use a question and answer format. We actually worked a little bit on formulating a few questions that might bring out the most interesting information for the group here. I talked with a bunch of the people here, I consulted with chatGPT, I talked to my wife, my kids, but we came up with about a dozen different questions. I’m going to shorten the list, and then, hopefully, open it up to live questions from the group, if possible.

Navin:

That would be awesome.

Dave:

First, if I might ask here, can you recount one of your experiences in the entrepreneurial world that it was most educational, most valuable, or most interesting? Then can you share some of what you learned, and how you got some out of that, and how you’ve brought that to Mayfield to allow Mayfield to make better investment decisions?

Navin:

Great, great. So for those of you who don’t know me, I have been doing venture capital for 20 years, but before I did that, I was on the bright side of the business called entrepreneurship. So I started my first company in ‘96, right out of grad school at Stanford, and my company was one of the first ones doing video streaming over the internet in software. And it grew like crazy in 18 months.

And the highlight of the journey was Microsoft – it essentially started as a partnership, and one thing led to another, and they said, “Hey, this is a core technology you need to come pitch.” I said, “Okay, but to who?” They said, “To Bill Gates.” I was like, wow.

You always hear about 10X Entrepreneurs. But when I went to this meeting with Bill Gates, I met a 100X entrepreneur. This was in ‘97, and the questions he asked were just amazing, and I keep those things to myself, and try to bring them into our startups.

One thing he asked me was, “What do you think is going to be your market share if we partner with you?” My answer was, “We should be in every Windows powered computer and every Windows server.”

Then he asked me the law of physics, which I failed, and then he asked, “What do you think is the amount of profits a number two player makes in an industry?” I said, “Maybe 30% of the profits.”

He says, “Nope, you’re wrong. The number one player in any industry makes money, number two breaks even, and there’s no number three.”

Then I go to Microsoft, and they’re in the war with Netscape. Fast forward, number one player makes money, there’s no number two, and then when Google Chrome comes, there’s only two players. You go back to Windows, there was Solaris, 100s of forms of Linux, down to two. One is freeware, the other makes money. You go to the mobile ecosystem, Apple makes the profits, Android is number two, there’s nothing else.

I learned the hard way that in order to win, startups need to first get mind share with their potential customers, then they need to get market share, and that will lead to revenue.

So if you have a land grab opportunity, don’t just think about short term revenues. Think about community, think about winning the mind share, and the hearts of your customers.

So I think those were some of the key lessons, but just meeting an 100X entrepreneur, or maybe 1000X, still gives me chills. I never had to pitch to Steve Jobs. I’m pretty sure he used to be like that too.

Dave:

A remarkable story. It’s something for all of us to learn from. Another question, if we might draw from your vast experience, can you just give us a brief history of Mayfield, and how you’ve progressed through the years, and some of the more exciting times in the firm?

Navin:

Yeah, absolutely. So this is the third generation of leadership at Mayfield. The firm started in 1969 by a gentleman named Tommy Davis. He actually started at another firm in 1961, Rock Davis, along with Mr. Arthur Rock who funded Intel, but then they split, and Mayfield got formed in 1969. Tommy Davis decided they were going to build a people first firm.

So what exactly does that mean? He wrote a book on how people make products, products don’t make people. He called it a one-man war, that hey, he didn’t come from the technology industry. He came from a legal background, fought in the Vietnam War, and he didn’t know anything about technology, he wanted to learn about technology, so he hung around with the smartest people at Stanford and named the firm Mayfield. Any guesses what Mayfield represents?

Any guesses? Maybe you? Some people think it’s the dairy company. There’s a company, Mayfield, then they thought it’s the Mayfield Bakery. No, it’s not. It’s basically the town of Stanford, before it was called Stanford, was called Mayfield. And then, it transformed, 100 years back or so.

So Tommy Davis essentially learned the business by just driving Dean Terman around. So he used to consult, and just understand what’s happening, and from that day, to today, with a 50 plus year history, the firm believes you need to be in partnership with great people, because ideas, markets will come and go. Look at NVIDIA, one of the most valuable companies in the world, fourth, or fifth-largest market cap. Started as a small company, was a fledgling for years in this ecosystem. Today it has a trillion-dollar market cap because it kept reinventing, kept pivoting.

So if you back great people, their initial idea or market isn’t going to matter, because they’ll pivot to find the right market opportunity. So as long as you’re patient, just partner with great people, who have a sixth sense, and have the tenacity to go through any wall to just make it happen.

So that’s what became the culture, and the ethos of the firm. Don’t get enamored by the tech and the market, because it’s all about execution. Genius is only 1% inspiration, so bet on people who are going to go through any wall – but ethically.

So I think that was the background, and the firm has been through its own ups and downs, and you learn from the mistakes. Learn from the mistakes, but do a lot of right, and if you keep partnering with great people, just good things happen.

Dave:

Remember that. So here’s Mayfield, been around for 50 years. We’re at Silicon Catalyst event here, so we’re all focused on semiconductors largely.

And I’ve been in the industry, well, for a lot of years, and I remember when venture capitalists in the Bay Area, and everywhere, were highly enthusiastic with almost no exception about investing in semiconductors. That’s not always been true for the past 20 years in particular. I’m really enthusiastic that Mayfield made a commitment to get more focused on semis, with its relationship with Silicon Catalyst.

And one of the questions that has come to mind, and came up in Silicon Catalyst discussions, is what goals do you have in the relationship, the partnership that you’ve announced with Silicon Catalyst, and what do you hope as a firm to achieve?

Navin:

Yeah, so Mayfield, I think, from the 1970s until around 2005, was one of the most active investors in the semis space. And then, VCs just bailed out, because it was really hard to build semis companies with the dominance of the X86 architecture, and it was just very hard for companies to raise money, get design wins, it just took forever.

And so with the VC fund life of 10 to 12 years, semiconductors became like biotech, and at the same time there was money being made in games, in social, so people ran for the hills. So some of us started re-looking at this area in 2014, 15, and started realizing, and people in the room know this better, that there’s going to be a plateauing of Moore’s law, unless there is some innovation in physics, or quantum physics, because at the end, you’re fighting physics. You can only pack so many transistors.

So we said, “Okay, if that’s the case, what kind of companies can get created? Yes, they’ll be capital intensive, but if the prize is massive, you should be funding them.”

So we coined, this term, the renaissance of silicon and we predicted that with the plateauing of Moore’s law, there’ll be a need for application-specific architectures. There’ll be a need for low power devices. With the prevalence of 5G, there’ll be new silicon coming out. Power and cooling will become a huge issue. All these trends were just emerging, and we realized if the Moore’s law is plateauing, you can only do so much in software.

Then we met with Pete and Tarun, and we agreed that aim number one is grow the semis entrepreneurial ecosystem. How do you foster more entrepreneurs to work on bringing silicon back to Silicon Valley? Right?

Number two, if Mayfield can help advise Silicon Catalyst companies, help them during the selection process, and of course in the right ones where it matches our thesis, fund them, then you’re helping Silicon Catalyst, and the broader ecosystem.

And then, being part of this rich community, hopefully, we won’t make the mistakes they’ve already seen. So we’ll make new mistakes, and at the end, in venture capital, it’s all about making that 100X, 1000X return, but you don’t need to reinvent the wheel, and make the same mistake.

So that’s what Mayfield gets in return. We bring a lot, but in return, our hope is Silicon Catalyst will not only advise our companies, but also keep Mayfield out of trouble of backing our own things, right? Because even though we think we have a thesis, that means nothing compared to industry experience. It’s just amazing to be part of this collective.

Dave:

Wow. I, for one, am glad that you’ve joined the Silicon Catalyst community. One of the questions that many people have posed to me, and requested that I posed to you, is that you recently raised a new fund. Congratulations, again, another billion dollars, or whatever it was. One of the-

Navin:

A little bit less. Somebody said, “You don’t want to be a unicorn VC, that’s why you did it.” I said, “No.” They said, “Great marketing.” No, we don’t need it. We could even raise two, three billion if we had wanted to. Companies should be unicorns, and often times even they shouldn’t. They’re imaginary figures, they’re not real. You need to build real companies.

Dave:

There you go. Real companies are where the difference is made. And the question that comes up is, out of that billion dollars, do you anticipate, or have discussions with the LPs that you brought into that fund, focused at all on semiconductors? Is there a positive attitude? Is there the governmental emphasis? I hear politicians can even say semiconductors, and silicone, and all these kinds of things, and do you think that semiconductors are going to be a focus for the new fund?

Navin:

Yeah, I think it’s a big focus for us. And here’s the thing. Having been in the business for so long, both as Mayfield, and me, there’s a lot of trust that we know how to spot great entrepreneurs chasing new markets or existing markets, and we have the capability to turn small boxes of money into bigger boxes of money.

Now, the thing is, the boxes itself at input have gotten bigger, but when you see multiple huge companies in the space like NVIDIA and AMD, you can dream that there can be five or 10 billion dollar companies that VCs can back in this ecosystem.

So Mayfield’s aim is we want to be one of the biggest VCs, who focuses on inception stage, and has the most dollars to work in deep tech. So both inception, and deep tech is like 50% of our focus, and deep tech doesn’t just need to be silicon. It could be systems, which are based on silicon. It could be MEMS based technologies. Why stop there?

Biology, synthetic biology is also deep tech. So what physics does, you can do it in chemistry for batteries. It’s a big unsolved problem for EVs, right? Look at the cost. Why won’t you want your car to run for 1000 miles? Why wouldn’t you want your phone to not overheat? So to me, I would push the people in the audience to think beyond just silicon, and say, can we go back to our roots, and look at innovation in sciences, look at innovation in physics, chemistry, biology, and bring the knowledge you guys have done in the silicon industry, and do it elsewhere.

And I think silicon, and silicon based systems, I think, will be 20 to 25% of our focus, especially with trends like IoT, AI, networking connectivity, and optical switching. It’s not in the data centers. You can’t do these things on X86. You guys know it better.

And so, I think there’s a lot of innovation to do, but having been in the business for so long, the key issue still is, who’s the buyer of the technology, and what do you do with the capital intensity of these companies?

So you need a follow on ecosystem, and you need people in the room who are at corporates to say, “Hey, let’s foster innovation so all of us win.” And TSMC is a good example. They are helping companies of all sizes. Clearly, they have to give preference to the trillion-dollar companies, but our companies hopefully can be one 10th of them. That’s 10 billion.

Dave:

But you heard them talk, they still love startups at TSMC, which is great to hear.

Navin:

Yeah, we love them. They’re great.

Dave:

Yeah. So I have to bring this up, generative AI?

Navin:

Biggest topic.

Dave:

Everybody’s talking about this topic. I’ve heard your thoughts about some of the specific investments in that area. Do you think that startups in semiconductors, or around semiconductors, have a chance of making a great return in that general domain, even in the face of the hyperscale companies doing what they’re doing, and the kind of money that they’re spending?

Navin:

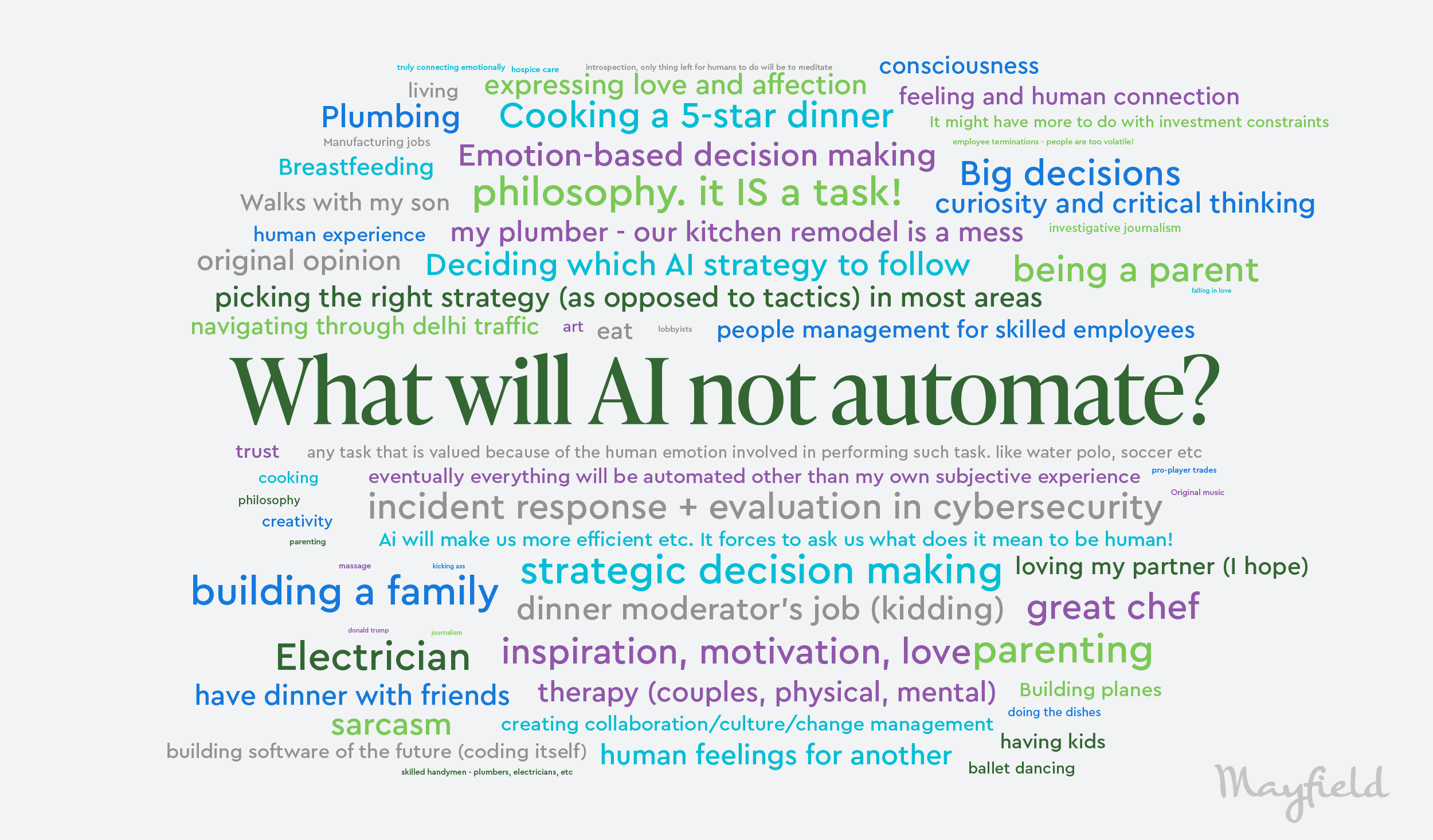

So I think, first of all I would say, not just generative AI, but AI is a real trend. Basically, we lived through the client server era, then the PC desktop era came, then came the web era with browsers, then came the mobile era, and the cloud era, so I think AI is a real thing. And either we are going to fight it, or we going to use it, and say at the end it’s a tool, it’s a technology, so humans should control it.

So there’s going to be a lot of innovation, and there’s going to be a lot of opportunities. Now, whether there are opportunities in silicon, whether there are opportunities in middleware, whether there are opportunities in systems, whether there are opportunities in applications etc is all still to be played out. I think applications are a white space. So could you have applications which don’t displace humans, but augment them.

Let’s look at security, let’s look at coding, let’s look at testing. There’s a shortage of talent in DevOps, in SecOps, so if you have 10 racks, maybe five you can fill, but five can be AI as your teammates. Now, you may not need five, maybe just equal into two. So at the apps layer we see clear, clear opportunity. Similarly, we see opportunity in middleware and tools to enable the mass market outside of cloud providers. Now, comes the hard part, which is like, what do you do at the silicon layer, right? Because half the buying probably is going to happen by three, four companies, the hyperscalers – and can they really depend upon startups, or will they go just work with AMD and NVIDIA?

So I think edge-based AI, where markets are fragmented, where Xilinx, and other people used to play, could be an interesting market. I think inference is still unsolved, but the big players are there. The question I’m trying to figure out is what is the end market? Because if you have concentrated buyers, like the cloud providers, they have too much power. They have proprietary software. If they port it into a startup, first it takes 18, 24 months, and then, the startup gets acquired by a competitor. You wasted all the time. They learn.

So you have to go find fragmented markets where just, because four people in the world can do it, can rest of the world do it? And I don’t think if AI is going to be like CPUs, that’s where the market is betting with NVIDIA. If it’s going to be everywhere, startups, and entrepreneurs have to go find markets where it’s not just four, or five concentrated buyers, and come up with a solution which optimizes your design, optimizes your solution to that need, and build channels which somebody may not be interested in doing.

So you can’t just say you’re going to go sell to Google Cloud, or Azure Cloud. They may not want to work with you. They’re happy with NVIDIA, maybe with the AMD, or they’re already building their stuff. And I think in AI, one of the areas is this connectivity between all these AI servers, which these people don’t do is an area. Edge is another area on the silicon side, I would say, so let’s keep an open mind, but I think going, and fighting, and saying, “I’ll take down somebody who already has 95% market share,” is like a fool’s errand. So go find new markets, new wedges, and remember you only need 1% of the market. Don’t go play in somebody else’s territory. Startups don’t do that.

Dave:

Keep that in mind, otherwise you’re on a suicide mission.

Shifting gears a little bit, before I try to open it up to some live questions here. A question that I’ve always asked people in the professional money management space, as much as anything else is. We’ve got a pragmatic situation. We’ve got, I don’t know, 30, 40 entrepreneurs here that will make 300, 400, 500 presentations to venture capitalists over the course of the next six to 12 months, probably.

Are there any particular words of wisdom you could impart to this community about what they ought to do, or ought not to do, in order to, number one, make sure they don’t turn off potential investors in their company, or more, to bring them in, to lure them in to their story.

Navin:

So I think every VC firm is different, and it’s hard to say what other people look at, but I can say some of the things Mayfield looks at, but some things I’m pretty sure every VC will look at.

So let’s go through what the industry will look at. The first thing everybody’s going to look at is, what market are you going after, and how big is it, right? It’s just a common thing people will ask. Second is people are trying to figure out, it’s not about the technology, and most of the people just get lost in that area, is to figure out, is your product really a painkiller, or is it a vitamin? Because people don’t have time, they’re going through a down economy, CapEx budgets are being slashed, IT budgets are being slashed, and you are number five in the priority. They don’t even show up.

You better be number one. Somebody has a headache, don’t tell them, right? “Hey, take vitamin C.” They’re interested in Advil, so sell something which is an Advil to them – figure out the need of the customer. As far as Mayfield is concerned, we look at those things, but I think the most important thing is be authentic, be yourself. VCs. You’re pitching to 35, 40 VCs. I see 2000, 3000 pitches a year.

So 3000 pitches a year, and you are looking for that as a firm. That’s what we do is, you have to keep looking, looking, looking, whether it’s Zoom, whether it’s PPTs, and other things, but you look for authentic entrepreneurs.

And don’t be coin-operated in the meetings. Try to be patient. Try to understand what this VC is really getting at. Don’t interrupt them, because answer the question they’re trying to ask. Don’t answer stuff that is not even important.

So I think those are some of the things I would say, yes, have your notes on market. And most VCs, do not build chips, we are not from this industry. We don’t know how to write this stuff, so don’t spend time there. Get them on the same page.

And the most important advice, I kept it to the end, is, guys, since we see so many pitches, you better get your message across in 30 seconds. So I always tell entrepreneurs, when you open the slide, be very clear. Why do you have the right to exist?

And then, after that, it’s your elevator pitch when you are on TV, right? It’s just the headline stuff – “I’m going to be X of Y.” Right? Because nobody has time to sit through 30 minutes. That’s why VCs will take out their phones, they’ll start taking notes, but it’s better to just get to the punchline.

Dave:

Thank you very much for that, and I thank you on behalf of the people here.

We have a little bit of time left so I’d like to open it up to live questions in the room.

Navin:

There’s one there.

Audience member:

Yeah. So you focused on Mayfield, focusing on humans, so what is the criteria you use to figure out if the founder is good or not?

Navin:

Yeah, I think that’s a secret, right? If I say that, then people will fool us, right? Okay, man, that’s the joke, so it’s very simple, right?

We are looking for authentic entrepreneurs, and we are going to spend enough time, not one hour meeting if you’re interested, 10 hours, 20 hours, till the entrepreneur gets tired, and we are really going to get to the bottom of, are these people thinking about themself, or the company? Entrepreneurs who use I, versus we, is a signal, and I hope you understand what I’m saying, right? So they’re company builders. They’re not like individual builders.

Second, they have just high EQ. Everybody has IQ. The EQ, the emotional quotient, is very, very high on people who build big companies.

Third, they’re very secure in their skin. They don’t get defensive, and they listen to the question being asked, and if they’re secure in their skin, they demonstrate vulnerability.

And then, they’re just amazing, amazing, amazing team players. Because to build a company, it’s not about your intelligence, it’s not about your individual hard work, it’s not about any of those things. It’s about leading teams, it’s about being authentic with investors, with your customers, and it’s not about you, it’s about the company. Support the company first, and believe me, it’s very hard to fool a VC who’s focused on that, right? We have psychology degrees now.

And by the way, these skillsets, people who are at GE, who are at many of the big companies here, you can’t grow in an organization then you are an IC. To become a leader of a company is the same.

Dave:

That’s a great answer. We have another question over here, please.

Audience member:

I’m curious about your thoughts on the advantages of having design and manufacturing of semiconductors in close proximity, and the implications, if any, due to the fact that much manufacturing capacity in the United States has moved overseas, the ability therefore to build world-class semiconductor companies here in the US now?

Navin:

Yeah, so this is more economic, so where I think the proximity to is more important, at least in my opinion, is to your customers. So the design, and the product management needs to be very close to where your customers are.

So if your customers are in APAC as an example, and you are sitting, and designing a product, not engineering design, defining the spec, what is called an MRD, or a PRD in the old days, sitting in the middle of US somewhere, be close to your customer.

So if you are close to your customer, now, comes the problem. The customer has a supply chain in country unnamed, X, and you say, “I will build in the US.” Okay? So you just build your chip in the US, but their whole supply chain is sitting in some other place in Asia Pacific, or in Europe, or something. So I think you need to be close to the customer, and the customer supply chain.

Now, because of shortsightedness in the past, cost reasons, this reason, that reason, supply chains have moved. They have become global, and it’s going to be very hard to just change it overnight. So what it’ll come down to is not startups. I think it depends upon big companies. They need to move first, right? Startups have so many risks, for them to, basically, go take that risk now, will be very hard, because they don’t even have volume.

So I think it’s dependent upon many of the companies and the partners in the room to take the leap. And by the way, they are the ones who are going to get government subsidies, not our small startups, basically, they have the volume. So they need to lead the path to bringing manufacturing, and the supply chain here.

Dave:

Another question over here on the right-hand side.

Audience member:

Yes. Okay, thanks very much, great talks. My question is regarding more on the recent economic trend, and I think that, in general, VC investment are affected, or in the past few months, and I just wonder if you can comment on the probability deep tech and the semiconductor will behave differently? So I just wonder if you can comment on what you see in the past six months, and what you can expect for the next six months?

Navin:

Yeah, absolutely. Right. So I think if we look at the data, the amount of funding that happened a decade back before the correction, was one 10th, there was a time in 2011, 2012, startups used to raise 40 billion. 2021, that number went to 400 billion, then 2022, it came down to 200 billion, and then, it might come down again, right?

Here is the thing. I went in and looked at the data, and this is not seen by most people, actually, the number of new companies getting funded wasn’t changing. Its existing companies were raising 10X the capital, because all the Wall Street money came to Main Street, and they don’t go fund the companies which were presenting here. They focus on mid to late stage companies, and because of the inflation, the company which used to raise 5 million at seed, or 2 million at seed, they said, “Instead of seeds, will raise mango seeds, they’re bigger.”

Then they said, “Oh, mango seeds are not big enough. Forget about seeds, we’ll raise watermelons, not watermelon seeds.” They became even bigger. And so, number of companies, new ideas was the same. They just raised more money at inception, and then, they is 10X the money.

So I think, actually, jokes apart, this is a great time to be an entrepreneur, And the main reason is big companies have to focus on their business. They can’t just go and work on science fiction projects, which will make money nine, 10 years from now. Talent is available. There’s less money by VCs into the startup ecosystem, so if you have a great idea, along with a great team, your chances of success are actually higher, and for the next three, four years, if you are in product building mode, it’s great, because big companies budgets are slashed everywhere, besides some segments which are growing, but when you come out with your product, they’ll be again buying.

So it’s a perfect time, and great companies, most of the time, are not created in bull markets. They’re created in times of economic turbulence.

So I would say, right, basically, it’s time to get your parachute together, and jump from wherever you want to, and have the right VC partner who will help you.

Audience member:

So jump without a parachute?

Navin:

No, that I won’t advise that you can, I’ll get sued. That’d be bad advice.

Dave:

That is a great way to conclude. There are many of us who would love to sit here, and absorb your ideas for as long as we possibly could, but I know that you have a hard stop. We really, really appreciate the time, and the wisdom that you’ve shared with us here today, and we’ll let you get off to your next assignment.

Navin:

No, I think it’s a real pleasure to be here, and thank you Pete, Tarun, and thanks, Dave, for making this happen. Real pleasure. Thank you.